RiskVA

Texas Bug Races – Revealed 23 Apr 2008

A Confidential Report

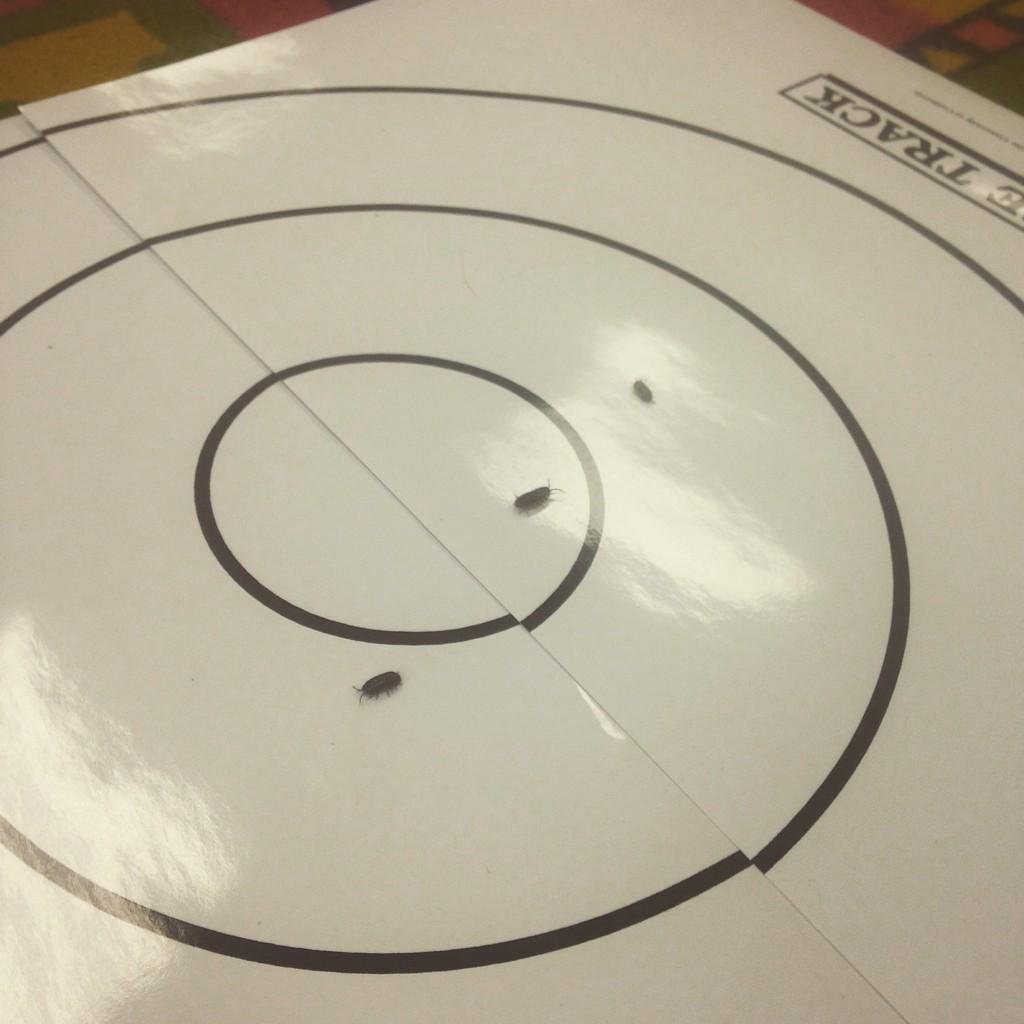

Tension mounted as race officials and owners gathered at the track. It was the last heat, and final tweaking was underway as owners warmed up their entries. Only moments remained until everyone would know who had the fastest bug. “On three, place your bugs,” the official shouted, and cupped hands hovered over the track. “One… two… THREE!” Four racers hit the dirt in the center of the circular track and two promptly rolled up into tight balls and quit. The other two were off, but not in a cloud of dust, even though fourteen pairs of tiny legs were pumping enthusiastically, well sort of. One of the sleepy or dazed bugs slowly unrolled and uncertainly began to walk. But it was too late. In about half a minute the winner crossed the circle that marked the finish line to a mixed chorus of moans and cheers.

These racers were, of course, not Volkswagen bugs, but pill bugs; little black non-insect arthropods related to lobsters. A half to three-quarters of an inch long and covered with overlapping “armor” plates, pill bugs live in moist environments under logs and rocks. They eat decaying vegetable and animal matter and help cycle nutrients into the soil. Each bug has seven pairs of legs.

Pill bugs, often erroneously called sow bugs, provided a favorite activity at school recess when I was a boy growing up in Texas. We called them doodlebugs, another misnomer. But we didn’t care about scientific accuracy, just vigor, and speed. A bunch of us would collect some of the harmless critters from under logs or rocks and speed test them. The slower ones were discarded (returned to their homes safe and sound) and the fastest were carried to the bug race site in a little box or paper cup. A circle about 18 inches in diameter was drawn in the dirt and entries were dropped in the middle of it. We held the racers in our hand for a few minutes before each race to warm them up. Being cold-blooded, they ran faster when their body temperature was higher. A hot bug was a fast bug.

Bug Racing a Crime

Possession of pill bugs was a crime under the school rules, most likely based simply on the fact that anything fun was off limits. Some things never change. Besides, we occasionally dropped a couple of the little roly-poly crustaceans down a girl’s blouse. Today, of course, that would be called sexual harassment or molestation or maybe even aggravated assault. Nowadays we’d have to drop an equal number down guys’ shirts to avoid the sexual accusation, but the assault charges would likely still apply – not to mention automatic expulsion and exile to a “special school.” To make matters even worse in today’s terms, we also collected more of them than we needed and kept them in little herds for trading purposes. Whoops! That’s possession with intent to distribute. And don’t even start on animal rights! Life was simpler then.

Biology 101

Pill bugs get their name from the fact that when disturbed they roll up in a tight ball about the size of a small pill. The tough plates on their back, much like those of an armadillo, protect their soft undersides. In fact, this similarity is reflected in their scientific name, Armadillidium vulgare. Varying in color from gray to brown to black, and sometimes called woodlice, these tiny animals breath through gill-like structures, requiring that they remain moist. Dry conditions will kill them.

As they grow, like their lobster relatives, pill bugs periodically shed their tough outer covering. The interesting thing is this molting is accomplished in halves – first the back half and then two or three days later the front half, often resulting in a bug that’s two-toned.

A Deep, Dark Secret

Pill bugs are entirely harmless, so dig around a bit and see if you can find any. Keep your racers in a plastic, ventilated container with a moist piece of paper towel until post time. Then after the race, put ‘em back where you originally found ‘em. They’re an interesting part of the fields and forests of much of the United States and many other places in the world. Happy racing kids – young and old. But if you get caught, don’t tell nobody nuthin’. You never heard this from me and I never saw you, man.

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.