RiskVA

Worm Grunting is an Old Southern Tradition 9 Dec 2015

One afternoon some years ago in the campground at Ratcliff Lake I saw people clustering around a crouching man. The group of folks jockeying for a good view told me the fellow was grunting for worms. Although I listened, he didn’t seem to be grunting, snorting, wheezing, or even breathing very hard. What I did hear was a rattling or ratcheting sound. He had driven a notched wooden stake into the ground about 8 inches and was rubbing another stick up and down it, producing a rattling sound. My informant said some folks called this process “rattlin’ up worms” rather than “gruntin’ ‘em up.” The rattling continued and this strange fellow, whom I now was sure needed psychiatric care, assured his audience that worms would soon pop out of the ground like jumping beans.

Oh boy! I began to slowly back away, hoping I hadn’t been accidentally trapped in the middle of an off-beat cult. Then it happened. Wriggling and wiggling, at least two dozen worms, followed by others, began to emerge from their burrows, crawling out full length on the surface where they were immediately scooped up by the now vindicated worm hunter.

Grunting techniques vary. Some use a smooth stake pounded into the ground across which they run a notched stick like the bow of a violin. Others say thumping a shovel repeatedly on the ground works. And Frank Shockley, a former colleague in the then College of Forestry at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas, said he rubs a brick across a stake in the ground and has success.

It turns out that humans may not be the only worm grunters around. Apparently, several kinds of birds do it too, in their own special way. But strangest of all is the story of “The Wood Turtle Stomp” reported by John H. Kaufmann in Natural History Magazine, August 1989. A male wood turtle was slowly walking through the forest rocking back and forth.

It turns out he was stomping his front feet on the ground as he moved along – left, right, left, right – do the Turtle Stomp! Then he would suddenly duck his head, grab a worm and eat it. Kaufmann is sure the turtle was grunting for worms.

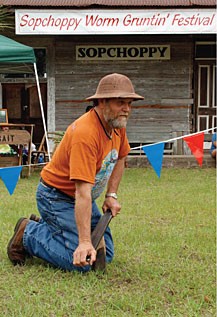

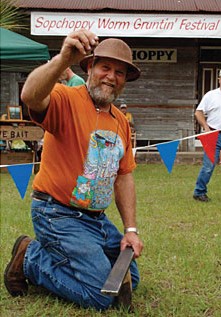

It turns out that grunting for worms is widespread and has been practiced in the south for years. In Florida, for example, commercial bait suppliers drive a gum, cherry, or hickory “stob” as far as 3 or 4 feet into the ground. Then a section of steel leaf spring from a car, about two feet long, held like a wood plane, curve down, is “scrubbed” or rubbed repeatedly across the top of the wooden stake with the grunter leaning hard on the iron tool. Each stroke produces a deep, vibrating “rrrronk!” sound that Kenneth Brower, writing in The Atlantic Monthly in March 1999, said made the soles of his feet tingle four feet away.

According to Brower, one operator gathered up to 10,000 in a single day. With current prices at $25-$30 per 100 night crawlers, that totals up to as much as $3000! And that ain’t chicken feed. Kim Hiss, writing in Field and Stream, reported that 76-year-old Lossie Mae Rosier “started worm grunting in 1950 and raised 11 children on the money that the bait brought in.”

In Sopchoppy, Florida, 45 miles south of Tallahassee, worm grunting is so popular locals hold an annual Worm Gruntin’ Festival and Dance. Held on or about April 10th each year, the festivities draw several thousand people. Go to www.wormgruntinfestival.com for more details.

Why worms flee from their homes when they feel certain vibrations is anyone’s guess, but one widely held theory is that the grunting feels like a mole or worm-eatin’ shrew digging its way toward a succulent gourmet meal. Run for your life, guys, its Monty the Menacing Mole!

In any case, the practice is fascinating, and if you have stories or experience with this method of annelid accumulation in the fields and forests, I would like to hear from you. Or, if you’ve never tried, give it a shot and let me know about your success rate.

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.